Home > Sports > Athens 2004 > Features

Olympic Legends: Teofilo Stevenson

August 12, 2004

For more than a quarter of a century one question has been put repeatedly to Cuban heavyweight boxer Teofilo Stevenson."Why didn't you accept all those million-dollar offers to turn professional?" the three-times Olympic champion is asked.

Essentially the answer is always the same. "What is a million dollars compared to the love of my people?"

Essentially the answer is always the same. "What is a million dollars compared to the love of my people?"

"Professional boxing treats a fighter like a commodity to be bought and sold and discarded when he is no longer of use," he once explained.

"I wouldn't exchange my piece of Cuba for all the money they could give me."

Stevenson, born in 1952 in a small town on the north coast, was invited to Havana at the age of 13 to train as a boxer.

Cuban amateur boxing, assisted by specialist Soviet coaching, was already formidable and Stevenson quickly attracted attention in the most glamorous of the divisions.

At the 1972 Munich Games, Stevenson hammered American Duane Bobick into submission then disposed of West German Peter Hussing to reach the final. He won the gold medal by default when Ion Alexe of Romania turned up with a broken thumb.

CLASSIC FIGHTER

By the time of the 1976 Montreal Olympics, Stevenson was at the peak of his powers, a classic combination fighter using his height and reach to full advantage and alternating a jarring left with thunderous rights.

His first three opponents lasted a total of seven minutes 22 seconds. Romanian Mircea Simon survived two rounds in the final by completely avoiding Stevenson. When he did get hit in the third, his corner promptly threws in the towel.

Four years later there were no Americans as the United States boycotted the Moscow Games after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the previous year.

This time Hungarian Istvan Levai became the first person to go the distance against Stevenson, who won a points decision in the final over Pyotr Zaev of the Soviet Union.

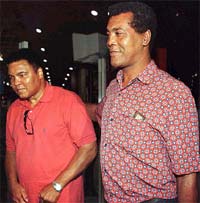

The American interest in the Cuban was understandable in an era featuring a host of great heavyweights, headed by Muhammad Ali, George Foreman and Joe Frazier.

Don King and Bob Arum were among the promoters who thought the tall, powerful and handsome Stevenson could add lustre to their ranks.

UNWAVERING

Stevenson remained unwavering, prompting the headline in a 1974 edition of "Sports Illustrated": "HE'D RATHER BE RED THAN DEAD".

"Given two, maybe three more years, he probably would become the heavyweight champion of the world," the article said. "But he most assuredly will not."

Stevenson's refusal to defect in search of capitalist gold brought him socialist rewards.

A grateful government gave him a two-storey house in Havana, two cars and a five-bedroom villa in the town of Delicias.

He was a hero to the Cuban people, including President Fidel Castro, and consistently praised the benefits of the revolution for the ordinary person.

Stevenson was beaten in the first round of the world championships by Italian Francesco Damiani in 1983 and his days appeared to be numbered.

Reports in early 1984 indicated he was training seriously for the Los Angeles Games but the Soviet-led boycott meant he was never to fight at the Olympics again, althought he went on to win a final world title in 1986.

Two years ago, Stevenson was asked by the London Observer newspaper why Cuban baseballers defected but not many boxers.

"Because they don't have to," he replied. "Because in Cuba, everyone goes to school. School is the light because when you go to school, you can see.

"They don't have to resort to boxing to earn money."

The author reported that Stevenson was "shockingly unchanged from the Apollonian giant who used to frighten his opponents halfway into submission".

The contrast with the many professional fighters permanently damaged by their trade, including Ali, did not need to be spelled out.