The Rediff Interview/ Abu Abraham

'Cartoonists should be liberals and radicals'

"Gin or beer?"

The legendary

The legendary Abu Abraham, 73, was playing the

perfect

host to Rediff On The NeT's Shobha Warrier at his

Trivandrum home. Matters, especially matters of art, he told her,

were best spoken over gin or a glass of beer. So which shall it be?

Unfortunately, our lady was a teetotaller, with a

pronounced weakness for tea.

So could a cup of the stuff be procured?

"What!" the cartoonist feigned surprise, "Tea at noon?"

But finally, it was tea that saw the interview through.

Seated in his magnificent

and much-talked about bungalow (designed by the celebrated Laurie Baker), Shobha

consumed cup after cup of superbly-made tea as Abraham, who

started his career as a reporter for The Bombay Chronicle in 1946 before

switching to cartoons (with stints at The Observer and The Guardian), spoke frankly and poignantly -- yes, like a cartoonist! -- about

his art and himself.

Before we move to the interview, a little more about Abraham:

Besides his drawings,

he has several books -- Abu on Bangladesh, Private View, Games of the Emergency and Arrivals

and Departures -- to his credit as well. He was given a special award by the

British Film Institute in 1970 for his animated cartoon film No Arks. Two years later, he was nominated to the Rajya Sabha. Now read on...

The last time we met was a few months after Rajiv

Gandhi's assassination. I remember you were so affected by the tragedy that you could not draw cartoons anymore.

It affected me very badly. If this is the kind of

politics we have, what is the point in drawing cartoons?

Cartoons are supposed to create tolerance, some

kind of moderation. Humour always softens the atmosphere.

Of course, there are vicious cartoons also. But generally a touch

of humour is supposed to give a sense of proportion to politics.

It affected me very badly. If this is the kind of

politics we have, what is the point in drawing cartoons?

Cartoons are supposed to create tolerance, some

kind of moderation. Humour always softens the atmosphere.

Of course, there are vicious cartoons also. But generally a touch

of humour is supposed to give a sense of proportion to politics.

Rajiv Gandhi's assassination was a shock to me not because

he was a great friend of mine. That way, I was

closer to Indira. I knew him only a little. But just the idea that

this could happen was a rude shock to me.

Anyway, when one gets

to my age, it is not easy to produce even sustained weekly cartoons. It takes a lot

to draw cartoons... a great deal of mental effort.

It can be very exhausting.

These days, I write. And that works out quite well. Since 1981, I do a

syndicated column for The Hindustan Times and various other papers. That

gives me enough satisfaction as I can express my views.

Did Indira Gandhi's assassination also affect you the same way?

After all, you were closer to her.

That was also a shock. But I knew she would

die. I had said so to my friends. Even to my wife, I said,

'She will be assassinated.'

Why? Because of Operation Blue Star?

Not only that. She developed hostility from both within and out.

Especially from the Americans. Even Rajiv

was not in the CIA's good books. Remember the assassination

of (Patrice) Lumumba? Now it has come out that CIA

chief Allen Dulles approved his 'removal'.

But the advantage the CIA has always had

was that things become public only 10 or 20 years later.

So they get away with it. People just say it is part of history and forget it.

What about your stint with the Indian Express

during the Emergency. A cartoonist needs a lot of freedom, so the Emergency must have been a difficult time for you...

Only in the beginning. There was pre-censorship for the first

three months. In those

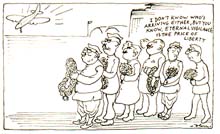

days, I did a kind of whimsical drawing. Sometimes it had hidden

meaning. In fact, I have published a book of over hundred such

drawings. It is called Games of the Emergency

It has my unpublished Emergency cartoons too.

Once the pre-censorship was over, I acted as though there was

no restriction. (C V) Narasimhan (the then Indian Express editor) also

wrote freely and

we got on very well. That was when I drew the cartoon of the President

in the bath which has become quite famous now. When there was

a challenge like that, I tend to draw better. It

was appreciated by the general public because there

was so much tension

those days. So, whenever they saw a good

cartoon, they just laughed loudly for a release.

What is the essential quality of a

cartoonist? A fearless mind?

(Laughs) Fearlessness, yes. In the sense that you express

only what you believe in. Cowardly behaviour is when you try to

please your editor or the proprietor or anybody else and draw

cartoons on subjects that you yourself don't believe in. That

happens sometimes when cartoonists go from one paper to another.

If you are honest to yourself, you feel a sense of freedom

and what you call, fearlessness. Cartoonists are privileged people

as there are very few of them functioning at a time. A newspaper

can't afford to lose a staff cartoonist. But if you start fearing, you don't take any risks.

You said cartoonists are privileged people. In what way? How

different are they from journalists?

Traditionally, the cartoonist has got away with

a lot of liberties. It was people like Domier and

David Low who established this tradition of freedom.

Without freedom, a cartoonist won't be able to really function. You will only produce

second-rate work.

Cartoonists have to think with

a certain amount of passion, have to respond and react to world

and local events whether it is poverty or corruption or

dowry or sati. But if a cartoonist

goes and accepts dowry, then he can't draw cartoons on that. In other words, cartoonists

should be liberals and radicals. All good cartoonists are like that.

You will seldom find a rightwing cartoonist. The middle group, yes.

For example Laxman, he is so

liberal centre. He is not leftwing. People like Vijayan are leftwing. Shankar was leftwing. It is difficult to place them right

and left. Generally, you have to have some radical thinking. But

if you are for the status quo, what is the point in drawing?

Cartoonists have to think with

a certain amount of passion, have to respond and react to world

and local events whether it is poverty or corruption or

dowry or sati. But if a cartoonist

goes and accepts dowry, then he can't draw cartoons on that. In other words, cartoonists

should be liberals and radicals. All good cartoonists are like that.

You will seldom find a rightwing cartoonist. The middle group, yes.

For example Laxman, he is so

liberal centre. He is not leftwing. People like Vijayan are leftwing. Shankar was leftwing. It is difficult to place them right

and left. Generally, you have to have some radical thinking. But

if you are for the status quo, what is the point in drawing?

You once said your best cartoons were drawn during

the Vietnam and Bangladesh wars. Was it because you were so disturbed

by the cruelty of it all?

Yes. Both were actually monstrous wars. The

Americans were going to 'take Vietnam back to the stone

ages' -- that was the expression they used. In Bangladesh,

it was pure massacre. I went to Tripura and saw what was happening

there. I wrote an article in The Guardian saying it

was actually cowardice not to intervene in the situation

which had created 10 million refugees.

In Delhi, there was

a controversy. It was Indira Gandhi's leadership and

those who were against her were against the Bangladesh

war. Then, people were being taken for a ride by the Western

embassies. I know journalists who used to come to

the Delhi Press Club and say it was all false propaganda,

that there weren't any 10 million refugees. I said, I was there, that there was no doubt

about it. It is a kind of scotch-stuff policy

that the Pakistanis were pursuing. There was a racist element

in it. The Pakistani Punjabis believed they were the

true Muslims and not the black Bengalis. It

is the other way round. They are one of the oldest community of

Muslims in the world. Conversion started in eastern India

soon after Islam was established.

Did you always go to places where the action was?

I have done that. Actually I was a major in the American army

during the Vietnam war. I was there in Saigon and they

took me in their planes to various places. I did a number of

articles for the Indian Express. I was made a major

because it gave me protection. And if anything happened

to me, my relatives would be informed soon. I must have been

the only major in the US army in kurta pyjamas (laughs).

Did you see a lot of action?

I didn't see any action on the ground. I went on a Red Cross

ship to see an exchange of prisoners. All along the coast you

could see flares dropping and bombs exploding. That was going

on. But outside Saigon, you could see all these peasant girls

harvesting rice while bombing was on at a distance.

But the girls were not bothered.

One could

see a lot of poverty and little girls begging. But they are such a dignified

nation. There was so much pride in even the children

who were selling flowers.

Was it why they could drive away the Americans?

They are extremely tough. They have this analogy about bamboos:

The bamboo bends, but doesn't break. And they use bamboo

for everything, for utensils, bridges... The bamboo culture

was perfectly suited to the war.

The Americans used to spent tonnes of bombs to destroy bridges. But the next

day, the bridges would reappear. They fought on a handful of rice

and dry fish while the Americans had these air rations, sea rations,

medical attention and all that. They fought because it was their

country. They are fiercely nationalist. It was an amazing

phenomenon. Like in Cuba. I always wondered how Cuba survived all

these years. They tried umpteen ways to kill (Fidel) Castro.

Did you see fierce patriotism in the Cubans also?

I would say so except there is one section which Castro

used to call the Cuzanos -- meaning worms -- who were so pro-American

and couldn't stand Communism. But Castro allowed them to go to

America -- and a lot of them went. So, there wasn't much of a fifth

column in Cuba. Also, that man's leadership is charismatic. People

just scream at the sight of him.

When did you visit Cuba?

In 1962. I went back again.

You seem to admire him a lot. You have

only his portraits here in your drawing room!

Sure, as a person. I am attracted to his charm

and fearlessness.

Shall we go back to your school days? I have heard you started

caricaturing your teachers when you were in school. Did they ever

see those drawings?

No. I didn't show them. (Laughs). Once I did one on a black

board but they didn't know who had drawn it. So I got scot-free!

In those days, did you ever think of becoming a cartoonist?

I was totally absorbed in drawing. But I didn't know how to become a

professional cartoonist. Besides, I had all the discouragement I needed

from my parents and

elders (laughs).

Was that why you decided to be a journalist?

I had to find a job. So when I went to Bombay, I tried to get

into a newspaper. But I had no idea how a paper functioned,

how reporting was done. I used to think reporters were sent

out in the morning to wander around and find news! (Laughs)

Everything was so baffling to me initially. I was an apprentice

for six months till I learnt where to find news and how to write it.

How did you find reporting? More interesting than

cartoons?

I don't know. Because, during my spare time I did cartoons for The Bombay Chronicle.

You joined the Shankar's Weekly as a

cartoonist later on. How

did you get the job?

Shankar saw some of my works in The Bombay Chronicle and

wrote to me. I was with a paper called Bharat started by Vallabhbhai

Patel and his son. By the end of 1951, I joined Shankar's Weekly.

Why did you leave for England? And you stayed for a long

time there -- nearly

13 years.

I thought I was getting a bit stuck with Shankar's Weekly.

Actually, I went on a visit to England just to get the feel of London. I wanted to see Paris also. In fact, I wanted to go to Paris more because I

knew French and was interested in their culture.

Was it a personal visit?

Yes. I organised some money. In those days, a passage by sea cost

only 53 pounds -- just Rs 650! You got four meals a day for 20 days.

Why did you decide to stay back? Were you so attracted to

London?

I thought my money would last for about three months. But it ran out in three weeks! But, fortunately, I found I could sell my work. In the first week, I sold five

cartoons, four to a tabloid called The Sketch. The one they rejected went into Punch. In those days, one could live on five pounds

a week.

I thought my money would last for about three months. But it ran out in three weeks! But, fortunately, I found I could sell my work. In the first week, I sold five

cartoons, four to a tabloid called The Sketch. The one they rejected went into Punch. In those days, one could live on five pounds

a week.

I continued as a freelancer

for two-and-a-half years. There was a magazine called The Eastern

World for which I used to do a bit of

writing and also cartoons.

But that was only once a month.

Then I met Michael Foot (later the Labour Party leader) who was

editing The Tribune and showed him my work. He

said, start on Monday. I did two cartoons in The Tribune. In the beginning of the third week, I got a letter from the

The Observer editor saying he was interested in

my work, so would I meet him? Till then, The Observer

had never had a regular political cartoonist in its whole history

of 150 years.

What about the other newspapers? Did they have regular cartoonists?

They had. The Observer was a very conservative paper. The editor told

me he was looking for a cartoonist

for three years. He said, 'Your drawings are attractive, you are not vicious, you

are gentle etc.' He didn't even know where I came from when

he wrote to me! I used to sign 'Abraham'. He thought I was a central

European emigrate, a Jew. That was in 1956, the time

the Suez operations took place. He said it wouldn't be a good

idea if I signed my cartoons 'Abraham' because I would be misunderstood.

People would assume I was Jewish. He offered me the job after

15 minutes. He asked me to sign a contract. So, I

stopped working with The Tribune. I was with The Observer for 10 years.

Photographs: Sanjay Ghosh

Tell us what you think of this feature

|