Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Lindsay Pereira

October 01, 2004

She sounds a lot like my grandmother. That's the first thought I have whenever Rupa Bajwa picks up the phone. It's a quiet, world-weary 'Hello' that comes across the line, all the way from Amritsar, where she currently lives. "Why do you sound so tired?" I ask, from the big bad world of Mumbai. "That's how I am," she replies, in a tone implicating me in the role of noisy city-dweller.

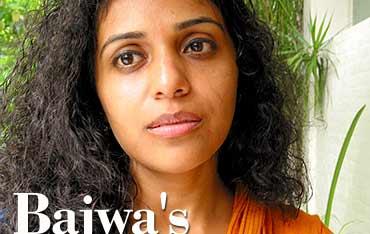

The photograph she sends me is of a young woman with a look that can best be described as pensive. There's a faraway look about her, and a faint, extremely faint, hint of a smile. It is from this combination of grandmotherly voice and pensive visage that comes the quiet violence of Ramchand, protagonist of Bajwa's debut novel, The Sari Shop.

It is a debut that came as a surprise to me, more because I hadn't expected such rich textures – crisp Bangladeshi cottons, dazzling kanjeevarams, soft chiffons, rustling crepes – or sudden streaks of violence when I first spoke to Bajwa, a couple of months before the novel was to be released. She was quiet, still grandmotherly, giggling as we spoke of life, literature, and the merits and demerits of alcohol. When I finally read The Sari Shop, the thing that struck me most was the incongruity of such a novel from the quiet, giggling Bajwa.

The novel documents the life and times of Ramchand, an orphan working at a sari shop in old Amritsar. Unlike the people he works with, he knows, instinctively, that his life is devoid of some larger meaning. A trip to the posh parts of the city reiterates this, prompting him to try and better himself at once. Studying English – with the help of, among other things, the Complete Oxford Dictionary and Complete Letter Writer – becomes the way out.

"He seemed to have appeared in my life on his own," says Bajwa, when I ask her where the idea of a salesman at a sari shop came from. "I had written some short stories a few years ago, and one of them was about Ramchand. The idea and character stayed with me. I could not write as quickly as I wanted to. I had to work towards taking some time off, saving money, and arranging other things. Finally, I managed to take nine months off to complete it. As the protagonist of the novel, I really like Ramchand very much."

It's difficult not to like Ramchand very much. He's simple, charming, and terribly naïve. There is something about him we can all identify with, whether it is his sense of helplessness or the feeling of inadequacy he is so prone to experiencing. He lives alone, in a tiny, messy room, with no one but his thoughts and the odd sexual fantasy for company. Companionship, for him, does not extend beyond Gokul and Hari, his colleagues at the shop. Life outside is rarely more exciting than dinner at a dhaba, a glass of mosumbi juice, or re-runs at the local cinema. It's a sad life, and we learn to empathize.

Bajwa has muted responses to questions about the actual writing process. Where do you do most of it, I ask. "In different places," she replies. "Every room I live in looks pretty much the same – lots of books, pens and paper, my alarm clock..." And what do you wear while writing? I persist, for no apparent reason but to annoy her. "Shut up, Lindsay," she says, muttering about shabby nightgowns and laughing about my threat to print that.

A lot of people have grown to like The Sari Shop. Some liked it so much that they nominated the book for the Orange Prize for Fiction, 2004 – a UK-based literary prize for women. While Bajwa's presence on the long-list (the English writer Andrea Levy won the prize for Small Island) was laudable, even more praiseworthy was the company she kept – Margaret Atwood (Oryx and Crake), Jhumpa Lahiri (The Namesake), Monica Ali (Brick Lane), Rose Tremain (The Colour), and Toni Morrison (Love).

There are two things about The Sari Shop that, in my mind, justified Bajwa's inclusion. First, it is her immense gift for characterisation. Ramchand, Kamla, Gopal, the Kapoors, the Guptas – they are all well-rounded, well-depicted folk, their idiosyncrasies intact. The author captures small-town life perfectly, from the products on display at grocery stores to dishes served at street stalls, the nuances of Hindi detective fiction, translations of film songs, to the importance of saving face that drives the richer women of Amritsar to collect crystal for its snob value.

Did she consciously aim for that realism, or did she want a psychological novel or novel of ideas instead? "This was a first attempt," says Bajwa. "I think no matter what the form or genre of writing, it's okay as long as the core is honest and makes sense to me. I like sense. I don't like nonsense, that's all."

She's not very comfortable discussing terms like Third World literature either. I point out that a lot of writers of fiction in India today opt for the genre of magic realism. Does economics play a role in this decision? Does it imply that Western audiences can swallow magic realism more easily than, say, a novel about grassroots reality? Bajwa is non-committal. "Someone asked me if I was 'pandering to Western readers'. To be honest, I have no clue what my neighbour wants to read, let alone readers anywhere in the world. I mean, how am I supposed to know?"

She asks me to italicise the 'I' in that last statement, telling me it denotes her desperation at questions like these.

Deciding to change track, wisely, I ask her if the novel's appearance on the Orange Prize long list came as a surprise, or if she expected the accolades. "I had heard about the Booker, not the Orange Prize," she says, "so it took me a while to register. As for the accolades, I somehow don't see them like that. I don't take compliments or criticism to heart."

The second thing that I think justifies Bajwa's success is her ability to depict the undercurrents that lie beneath India's seemingly chaotic reality. As Ramchand goes about his dreary routine, things happen. Situations reveal a reality radically different from what he has come to accept. He begins to realise, slowly, that all is not as it seems in quiet Amritsar. There are echoes of a horrifying past, a past that comes in the shape of Operation Bluestar. Then there is Kamla, the wife of one of his colleagues, who takes on the town's elite, blaming them for her husband's unemployment and the eventual collapse of her marriage. The treatment meted out to Kamla is swift, and shocking.

There is, for Ramchand, a sudden loss of innocence. It devastates him, propelling him into the first act of rebellion he has ever committed.

The novel leaves me with further questions. I ask about Kamla, and why she seems almost half-formed when compared to Ramchand. "I wanted her story to be slightly off-stage all the time," says Bajwa. "This was deliberate. Even till the end, Ramchand learns of her fate only through the other shop assistants; I don't describe what happens." I point to many female Victorian writers who used violent female characters that gave voice to their repressed alter egos. Are there parts of Bajwa in Kamla? "Not really," she says. "And if there are, there would be equal parts in Ramchand."

Rupa spent the first 18 years of her life in Amritsar, and began writing at 21. Today, for a 28 year-old, she hasn't done too badly. She is satisfied with the novel as a whole ("There is nothing I would have liked to add") and is hard at work on her next ("I would rather not talk about it.").

Considering her gift for capturing the nuances of settings and space, I ask if she has ever experimented with poetry. "It is a very difficult thing to do well," she tells me. "I have never had an urge to try my hand at it. And I am sure that if I did, the results would be pretty ghastly."

Rupa, my dear, I beg to disagree.

Headline Image: Uttam Ghosh