Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Shyam Bhatia

February 03, 2004

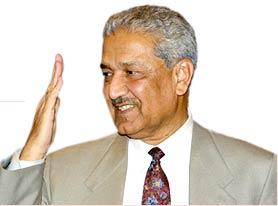

If Abdul Qadeer Khan could substitute his middle name, it should be 'hubris.'

At least, that is the opinion of those frustrated younger scientists who steadily leaked stories about Khan's luxury lifestyle to members of the Pakistani Opposition and others interested in what goes on behind the high security walls of the Khan Research Laboratories and allied centres of nuclear research.

It is, of course, the United States that has put overwhelming pressure on President Pervez Musharraf to clamp down on

Khan and make an example of him, so that others are not tempted to follow his example by selling weapons of mass destruction in the international marketplace.

Complete Coverage: Pakistan's nuclear bazaar

But Musharraf's decision to act has been assisted immeasurably by Khan's disgruntled colleagues within the nuclear establishment who are disgusted by the 68-year-old scientist's behaviour, including his use of crude language and greed that has made him one of the richest men in Pakistan.

It is these colleagues who are responsible for revealing information about the scientist's collection of vintage cars, his luxury homes in Islamabad and elsewhere, the real estate purchases in London, the grace and favour contracts worth tens of millions of rupees that were given to his former son-in-law, and finally, to crown it all, the Hendrina Khan Hotel he bought in distant Timbuktu and named after his Dutch wife.

In recent years Khan has boasted of how he is descended from Shahabuddin Ghauri, founder of the Slave Dynasty which ruled Delhi between 1206 and 1290, who is buried in Jhelum. Khan has spent millions of rupees refurbishing the tomb of his 'ancestor' that had fallen into disrepair.

By all accounts, there are no limits to his ego. Never satisfied with the many honours conferred upon him, he even suggested to a former Pakistan president, General Zia-ul Haq, that a major city should be renamed after him.

But the plans for calling a city Qadeerabad were put on hold after Zia instead renamed the Kahuta Research Laboratories after Khan, in apparent reward for stealing European uranium centrifuge enrichment technology and bringing it to Pakistan.

It was this enrichment technology produced by a three-nation consortium of the UK, Germany and Holland that Khan painstakingly copied over a period of six years and replicated in Pakistan.

The cascades of centrifuges that were built first in Sihala and then at Kahuta and other centres owe their existence to Khan's success in stealing the blueprints that explained how they could be manufactured and run at optimum levels to produce sufficient quantities of the priceless uranium that is at the heart of Pakistan's nuclear weapons programme.

After he left Holland in a hurry in 1976, his activities were monitored by the Dutch government, which launched legal action against him, by the CIA, India and Israel.

But Khan was lucky to have a powerful protector in Zia who became a favoured ally of the United States after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. As the leader of a front-line state confronting Soviet aggression, the US had a hands off policy where Pakistan was concerned. Khan's uranium cascades were always secondary to the more important task of

confronting Moscow and pushing Soviet troops back across the Afghan border.

To achieve these objectives the Americans at the time were prepared to overlook Pakistan's evolution as a nuclear weapons power. The status quo did not change when Pakistan first conducted a 'cold' test in 1987, followed by a series of actual underground explosions in 1988.

It took the 9/11 tragedies for US policy-makers to take a fresh look at the men behind the by now fast proliferating Pakistan nuclear weapons programme.

Suspicions hardened into certainty when US forces attacking Al Qaeda bases in Afghanistan in the winter of 2001 encountered a clutch of Pakistani scientists -- all A Q Khan protégés -- briefing Osama bin Laden's senior advisers on nuclear weapons technology.

Bin Laden did not have the infrastructure to make nuclear bombs in Afghanistan, but his Pakistani advisers seem to have briefed him about how to construct what is known as a 'dirty' radioactive device using stolen or bought material. A 'dirty' bomb can spread radioactive material over a large area using a conventional bomb.

Last year, under prodding from the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, the Iranian government conceded it had been assisted in its secret nuclear programme by Khan. In return, the Iranians gave him a villa and lucrative fishing rights in the Caspian Sea.

A year later, in January 2004, Libya confessed it too had a lucrative contract of mutual assistance with a gaggle of Pakistani nuclear scientists headed by Khan.

These revelations were topped by South Korea which told Washington that Khan had been detected taking nuclear know-how -- materials and designs -- to North Korea. A nuclear North Korea -- run by the erratic Kim Jong-il -- would threaten US bases and personnel throughout the Far East.

The Iranian and Libyan disclosures along with the threat to American lives is what finally provoked the US to move against Khan. Musharraf was told he needed to make an example of Khan or risk being ousted from office.

So far, Musharraf has chosen the former course. Pakistan's fundamentalist Opposition parties have threatened to turn out in their hundreds of thousands to protest the treatment of Khan, a national hero. Musharraf has told them and any remaining supporters of Khan that he will face them down.

Judging by the way some of Khan's former loyalists are willing to turn 'approver' with never ending tales of his folie de grandeur, Musharraf has plenty of ammunition available for use against the 'descendant' of Shahabuddin Ghauri.

Photograph: FAROOQ NAEEM/AFP/Getty Images

Image: Uday Kuckian