Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Priya Ganapati in Magadi, Karnataka

September 16, 2003

Part I: Bonded to the loom

Part II: Back to school

At one time, Karnataka's Magadi district was famed for its silk mills. It was also infamous. Many of the workers in these factories were children.

But the Magadi Makkala Dhwani project, launched with UNICEF's co-operation, to eradicate the use of child labour in the district's sericulture industry has altered Magadi's social and economic fabric.

The awareness created by non-governmental organisations and the notoriety the district has acquired for using child labour has seriously affected the sericulture business. Today, fewer parents send their children to work on the 'uri machines'. Factory owners can no longer claim to be ignorant about the laws against child labour.

"Today, if you go to any factory and ask them about the kind of labour they use, the first thing they will say is everyone we employ is over 14 years. They have come to realise that 14 years is the magic age," laughs K S Saroja, director of Chiguru, one of the four NGOs that are part of the Magadi Makkala Dhwani project.

But as child labour becomes increasingly difficult to employ, factory owners are seeing their profits shrink. Byranna, a silk twisting and winding unit owner, says he leads a hand-to-mouth existence today. With two school-going children and four adults to look after, he claims he now makes barely enough money to make ends meet. "If I find a job that pays me Rs 3,000 a month, I am willing to close down the factory. But at my age it is impossible to get a job," he says.

Though he claims to employ no child labourers, he says parents still come to him and ask him to put their children to work. "I say no. But that doesn't mean the children are not going to work elsewhere. If they are put to work at wine shops or hotels, they will develop a lot of bad habits. At least in the silk factories they can work hard and will have decent habits," he says.

Liberalisation and the consequent opening up of India's markets have had its repercussions in Magadi. China Rayon, a fibre that is thicker and cheaper, has replaced the more fragile and expensive pure silk threads. Many looms that once depended on pure silk thread now use China Rayon.

"The government is not providing us with any support," says M H Ranganath, president of the Magadi Silk Twisting Association. "China Rayon is eating into our markets. Exports have almost disappeared. There are barely 30 units left in Magadi. The NGOs have also created a bad name for the district. They have taken away all the business."

Ranganath lays the blame for Magadi's economic downfall squarely on the NGOs. "They cheat and exaggerate. Where there are two children, they will say there are 20. They have ruined Magadi because they want to create money and fame for themselves," he says.

Life has certainly become more difficult for the factory owners.

Power, for one, is no longer easy to pilfer.

In 1998, when Samashti wanted to find out the number of factories in the area, it first got a list from the local electricity board. Later, it found the list had barely 50 per cent of the existing factories. The rest were tapping power illegally.

With stricter monitoring by the Karnataka State Electricity Board across the state, power is no longer easy to steal and many units have shut down.

Today, Magadi is changing not just because of the government's co-operation or the NGOs' dedication or UNICEF's contribution -- it is changing because of all three factors.

"If the government decides, it can make a change," says Suchitra Rao, UNICEF coordinator for the project. "The Magadi project is the way things ought to be, where everyone works together in the best interests of the people. We have definitely had problems with the government, but without their help we could not have done so much."

Despite the apparent success of the project, the journey is not over yet for either the NGOs or the children.

Rao and her team would love to see the Magadi project replicated in Karnataka's other districts like Ramanagaram or Chennapatna. But to put together a project like the Magadi Makkala Dhwani, which has cost Rs 75 lakh [approximately US $163,750] over five years, is not easy.

"It will take another UNICEF to come up with that kind of funding," says Rao. "Maybe the government itself can do it. Magadi has shown them how."

UNICEF funding for the Magadi project ends in December. Chiguru doesn't know how they will fund the project after that. Saroja spends a lot of her time these days networking, trying to get some more funding. She is confident the work will go on.

"We are looking at a number of international agencies for funding. We will continue to work in the areas of development and adolescent children. We will definitely get some money. But there is no denying we are a below-the-poverty-line kind of NGO," she says with a grin.

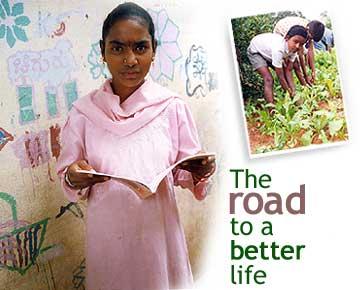

For the children, however, the road to a better life has just begun.

Shivakumar (see part 1), meanwhile, has been living at the Don Bosco home for a couple of weeks. He says he would not like to go back just yet, but he is sure he definitely wants to return home some day. Since the time he ran away, his parents do not know where he is.

"I don't want to go home because they will put me back to work," he says. "I want to study. My father, I am sure, doesn't care about me. But my mother must be crying everyday thinking about me."

Father Varghese is willing to take the boy home soon, but before that he has to fight with the local government for a few hours of power supply everyday. Welding (see part II) cannot be taught without electricity.

"The phone here is dead. We get no electricity and it is difficult to teach the boys welding. We are trying to grow our own food. The main thing is that the boys are happy here," he says.

Ananth's mother comes to meet him frequently. Chiguru believes she has left the boy in the residential programme because she wants to avoid the responsibility of bringing him up.

Vikasa's volunteers are glad to take care of him. But Manjuswami, Vikasa's co-ordinator for the project, and his team also need basic facilities. They don't know for how long they can continue living in the abandoned factory. As long as the government is supportive of their efforts, they say, they are unlikely to be evicted. But the children would undoubtedly love to have a better home.

"We don't know what will happen once the funding ends in December," says Manjuswami. "There is no job security attached to this work. But we have the satisfaction of having provided these children a future."

Lakshmi, who has been living in Chiguru's hostel for three years now, wants to be a dance teacher when she grows up. For now, she twirls around the single big room where nearly 60 girls live and sleep. A few weeks ago, her dance performance was appreciated in an inter-school competition. Next week, she will play kabaddi at the district level.

She has almost forgotten the 'uri machine'. That is the past, dredged up only for visitors and the media.

Part I: Bonded to the loom

Part II: Back to school

Photo credit: Omprakash

Image: Uttam Ghosh