|

|

|

|

|

| HOME | NEWS | INTERVIEW | |||

|

March 14, 2001

NEWSLINKS

|

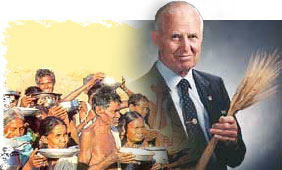

The Rediff Interview/Nobel Laureate Dr Norman Borlaug

At 87, he's still got a grip like a vise. And his eyes, despite the glasses, haven't lost their twinkle, or their fire. Yes, he's slightly hard of hearing, but you wouldn't know that because he's become an expert at lip reading. He maintains a grueling daily schedule that would put many a young men to shame. Meet Dr Norman Ernest Borlaug, Nobel Peace Prize winner, father of the Green Revolution, scientist, agriculturist, forester, farmer, but more importantly, a man with a mission: to alleviate hunger. To ensure that no one ever dies hungry. Ever. He was in India recently on a whirlwind week-long tour, visiting Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana to promote new varieties of fast growing high protein maize. He also found time to meet the President, the prime minister, the agriculture minister and, of course, the crème of Indian agro-scientists. In between, he took time out to grant an exclusive interview to Senior Associate Editor Ramananda Sengupta, to talk about where he comes from. And where he's headed. Would you like to start by telling us a little about yourself? I grew up in a small town in Cresco, Iowa. It was so small that I went to a one-room school for eight years... one room in which you had five year olds and seventeen year olds, and everything in between, all sitting together. My parents owned a small farm, and I and my brothers would help them. After school, when I joined the University of Minnesota, it was during the worst days of the economic depression. I had only enough money for the first five months. But I got myself jobs, helped out at the labs… and managed to get a first in forestry. I joined the US Forest Service, and on one of my assignments, I was said to be the most isolated member of the service, hundreds of miles from civilisation. But though I love forests and roughing it out in the wilderness, it's wrong to expect poor people to live that way, and like it. Anyway, I returned to university and graduated with a degree in plant pathology, and then joined Du Pont as a microbiologist. That was my first real job, though I did work for the forest service earlier. Then the Rockefeller Foundation offered me a job, and I was selected as part of a team going to Mexico to try and help solve their food problem. But what brought you to India? In 1960, The FAO sent me on my first trip outside the Americas. They wanted us to go to places where there were food shortages, not surplus, and so I went to Algeria, Pakistan, India. Libya, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Afghanistan… But then I came back in 1963 to India, and kept coming at least once or twice a year for a long time after that. And let me tell you, I've seen some dramatic changes. But I also want to point out that while you've done well, you have huge stocks of grain which could not have been imagined even a decade earlier, there are still people going hungry as they do not have the purchasing power. So now, your focus has to be clearly on distribution. In other words, you have try and put the surplus into hungry stomachs. How do you react to accusations that using bio-technology in food could have possibly dangerous repercussions? Let me put it this way. People are always scared of change. Change frightens them. But we need to educate the people about the benefits that the change will bring them. And that is why we need to mesh various branches of our sciences together, so that the people who do not know much cannot scare others. Besides, Mother Nature has crossed species barriers, sometimes even between species. Wheat, for instance, is the result of a natural cross long before man knew about cross breeding. What we are doing is only to facilitate this. Take today's modern red wheat. This is made up of three groups of seven chromosomes, and each of those three groups of seven chromosomes came from a different wild grass. So the modern bread that we eat, the wheat for it comes from nature itself crossing three species barriers, a kind of natural genetic engineering. I see no difference between the varieties carrying a herbicide resistance gene, or other genes that will come to be incorporated, and the varieties created by conventional plant breeding. I think the activists, who don't know much about the subject, have blown the risks of biotech all out of proportion. What about arguments that organic farming is a better option? That's a stupid assumption to make, though people are entitled to their own opinion. First of all, even if we used all, and I mean all, the animal manures, the human waste, the plant residues the organic material in the world as fertiliser, it couldn't feed more than half the world's population. And imagine the kind of land you'd need if all agriculture was organic. Cropland area would have to be increased dramatically, and that in turn would mean cutting down more and more forests. Are these environmentalists comfortable with that? Again, right now, nearly 80 million tons of nitrogen nutrients are used annually. If we were to try and produce this organically, you would require at least 5 or 6 billion more heads of cattle just to supply the manure. How much land would you have to sacrifice just to produce the forage for these cows? There's a lot of nonsense going on here. But it's up to people to believe that the organic food has better nutritive value. But keep in mind that there's absolutely no research that proves organic foods provide better nutrition. So if some consumers believe that organic food is healthier, God bless them. It's a free society. But don't tell the world that we can feed the world's population without chemical fertilizer. That's when this misinformation becomes dangerous and destructive. Design: Dominic Xavier

|

||

|

HOME |NEWS |

CRICKET |

MONEY |

SPORTS |

MOVIES |

CHAT |

BROADBAND |

TRAVEL ASTROLOGY | NEWSLINKS | BOOK SHOP | MUSIC SHOP | GIFT SHOP | HOTEL BOOKINGS AIR/RAIL | WEDDING | ROMANCE | WEATHER | WOMEN | E-CARDS | SEARCH HOMEPAGES | FREE MESSENGER | FREE EMAIL | CONTESTS | FEEDBACK |

|||