|

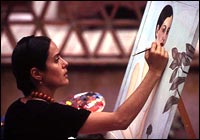

Salma Hayek owns her role

The subjective colourisation of history in Frida both informs and diminishes

|

Jeet Thayil

Frida Kahlo has become an iconic figure in recent years. She is revered as much for her art as for her unique personal style.

Since her art often consisted of obsessive self-portraiture, it is understandable that the image of Kahlo is everywhere --- from feminist postcards to lunch boxes. She is portrayed in Mexican peasant skirts, wrapped in antique rebozo shawls, wearing rings and flounces, in hair weaves and riotous headgear, always with her singular single eyebrow.

There has been a flood of recent material in tribute to Kahlo's work. Her paintings have set auction records, new demand fueled by celebrity collectors and museum curators. The US Postal Service has issued a commemorative Frida Kahlo stamp. There are hundreds of web sites dedicated to her memory.

There is even a site that propagates 'Kahloism', which is defined as "a religion that worships Frida Kahlo as the one true God." All Kahloists, the site goes on to specify, must have a shrine to Kahlo in their rooms. Moreover, they must "pray to it on a daily basis." Kahloists must be involved in the arts. They have to abide by a strict dress code: "only incredibly sexy or very unique clothing is allowed."

What is it about Kahlo that inspires such devotion? The biopic Frida goes some way to answering that question. The flip side of that kind of iconisation is sanctification. The movie makes a saint out of Kahlo and that is unfortunate. Kahlo was interesting precisely because she was no saint. She flaunted her flaws, especially the physical ones.

Certainly a core part of the Kahlo legend has to do with her long collaboration and partnership with the muralist Diego Rivera. The Rivera-Kahlo connection lasted from their first meeting in 1928 to Kahlo's death in 1954. Frida tells their story as if it were an epic love poem.

Their tempestuous union produced an avalanche of doctor's bills, divorce lawyers, temper tantrums, love triangles, gossip and tragedy, but it also produced an amazingly diverse range of work by both Rivera and Kahlo. And it is the art, constantly present in the movie, which energises and transforms the screen.

Salma Hayek, as Kahlo, owns the role. She brings more than characterisation to Frida. Hayek is also the film's producer and was responsible for the casting of Alfred Molina as Rivera and Geoffrey Rush as Leon Trotsky. She was instrumental in getting Julie Taymor to direct the film.

Taymor, whose previous work included The Lion King on Broadway has drenched the screen in colour. There are set pieces that dazzle the eye as monkeys, parrots, peacocks, and a surreal life-into-death dance-montage of Mexico shimmy across the screen.

Taymor, whose previous work included The Lion King on Broadway has drenched the screen in colour. There are set pieces that dazzle the eye as monkeys, parrots, peacocks, and a surreal life-into-death dance-montage of Mexico shimmy across the screen.

In a sequence about the early accident that crippled Kahlo and colored her life and work, Taymor uses motifs from Mexico's Day of the Dead festival. Little death's heads puppets move to music, as a giant jigsaw takes shape before the viewer's eye. It is a virtuosic moment that tells us Taymor knows her chops and is not shy about showing them off.

A New York sequence uses Kahlo's surreal style to produce a collage of Rivera and Kahlo taking in the sights, smells and sexual possibilities of the big city. Stock footage of trips that the two artists took and period documentary pictures are juxtaposed to create a sort of live three-dimensional painting. The scene is a work of art quite independent of the movie.

My only objection to the film is the canonisation of its subject. Rivera is portrayed as a sort of sacred monster. He is a coward and a womaniser whose only redeeming feature is his art. Kahlo, on the other hand, may be as promiscuous as Rivera, but for Taymor and Hayek, she can clearly do no wrong. This subjective colourisation of history informs and diminishes the movie.

Tell us what you think of this review