Home > Business > Special

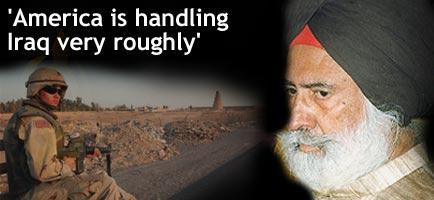

Haridarshan Mejie |

September 18, 2003

Haridarshan Mejie is a 73-year-old Indian businessman who has had professional ties with Iraq for the last 25 years. He has done $250 million worth of business with Iraq in last five years.

His construction company PCP International works with the United Nations in Liberia, East Timor, Kosovo and Afghanistan.

Mejie says Iraq is where his heart lies; he calls it his second home. He says the Iraqis consider India the most favoured nation to do business with and says he is pained to see how the country has been destroyed by America.

He is currently working as a special advisor to FICCI's Iraq cell.

In this first person feature, exclusive to rediff.com, he reveals the pain of a nation under occupation:

I was witness to the eight-year-long war between Iran and Iraq and the first Gulf war. We were in Basra then, which was a war-torn region.

Many businessmen in Baghdad were able to see America's designs on Iraq well in advance. Almost nine months ago, before America attacked Iraq, we warned Saddam Hussein to change his ways. He was our hero. In the Islamic world, most rulers are despotic; why blame Saddam alone? Take Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan -- are the rulers there democratic?

I was brought up in Jodhpur, Rajasthan. I remember how my people used to prostrate before the ruler of Jodhpur. So let us not debate whether Saddam was a dictator or not.

I sent a note to him through the chief of the presidential Dewan and through a member of the Revolutionary Central Council. We wanted Saddam to accept the United Nations inspectors. We wanted him to accept Pakistan's constitution, which allowed for multi-party rule, but where the president still wields the real power.

Since America supported Pakistan's president [General Pervez Musharraf] and his way of ruling, Iraq could have adopted the same system. But before Saddam could change, the Americans went ahead with their plans. War became inevitable.

I left Baghdad on March 14, just before the war; the 16 Indian employees who remained behind were later shifted to Jordan with United Nations help. I returned on April 28 with my manager Kamal Raj Purohit, who is in charge of my business in Iraq.

At that time, there was much hype about the reconstruction that would be needed in Iraq. Before I left for Baghdad, I formed a consortium of Indian companies willing to work in Iraq. I also met Bechtel [the US construction major] officials and other companies in Britain and America. Everyone was asking me the same question: What is the situation in Iraq like?

I reached Baghdad through Aman; we drove to Baghdad in a group of 20 for safety reasons. A four-lane highway that is almost 1,000 kilometres long links Iraq and Jordan. Once you enter Iraq, you travel around 600 kilometres on this highway to reach Baghdad. We drove in a group; everybody drove at the same speed once we entered Iraq. The American army was guarding the border. They just matched our faces with our passports. They don't check visas even now.

When we reached Baghdad, we found my office and the guesthouse where I live undamaged. My Iraqi staff were fine; they had guarded my property well. There was no electricity in Baghdad, but we have a large generator; its capacity is huge enough to light up a whole mohalla for eight hours a day. It was used in our absence.

We always had an excellent relationship with our neighbours. They reciprocated during the war by protecting our property with AK-47 rifles that we supplied to them for this purpose.

On reaching Baghdad, Purohit and I started looking for the Iraqi officers with whom we did business. We were aghast to see how the trade and civil supplies ministry had been destroyed. Except the department of oil, all the Iraqi ministries had been completely destroyed though there was apparently very little collateral damage during the war.

We started looking for senior officials like the director generals of these departments. They told me the Americans bombed the infrastructure heavily. Then, at each place, hordes of people came and plundered. Then, each department was burnt using some chemical.

The Iraqis claim the people who burnt the government offices were not Iraqis; they came from Kuwait. I don't know how it happened or why the departments were allowed to be destroyed. No paper, no document is left. We found our friends and other important officials walking on the roads or sitting at odd places.

Many director generals of different departments were overjoyed to see me. I was the first foreigner to meet them after the war. I was anxious about the Iraqis I knew; I wanted to know whether they were safe or not. Indian embassy staffers soon arrived from Aman.

We started looking for the Americans who were in charge of Iraq. Jay Garner was the chief of the American civil administration. His office was in Saddam's Republican Palace; Saddam used to live there until the first Gulf war. Then, his son Uday lived here. This palace was not bombed much during the war.

The guards at the gates were surprised to see foreigners like us. An American brigadier fixed my appointment with Garner for the next morning. I wanted to share what I had experienced in my three days in Baghdad with Garner. I was pained to see how the city had been destroyed and the psyche of the Iraqis had been damaged. My Iraqi friends were painfully discussing the behaviour of the Americans and their future plans. I prepared a note for Garner.

I wanted to appeal to Americans in the highest places and tell them not treat Iraqis as Arabs. There is a world of difference between the two. If you talk to the Iraqis, they will proudly remind you proudly that they are not Arabs. They have their own distinct culture and it is quite different from that of the Arabs, most of whom are Bedouins. Besides, Iraqis have a much higher intelligent quotient. They learn new skills quickly. They are educated and know the world. These qualities put them in a different category when compared to many other Islamic nations.

But the Americans are handling them very roughly. The day before I met Garner, I saw the American army personnel moving around in Bradley tanks outside my home. I was sitting in the open yard, trying to call Dubai through my satellite phone.

I heard guns being fired. A restaurant was being plundered just 100 yards away. The looters were people without jobs; they were desperate because they don't have salaries.

An American tank was standing just outside my gate. I drew the attention of the soldiers to the looting that was taking place before their eyes. A soldier atop of the Bradley showed me his collar, 'I am a corporal in the tank unit,' he told me. 'I am allowed to shoot only if someone is shooting. I can't do anything here.' He could not stop the looting because he was not instructed to do so! "

Haridarshan Mejie spoke to Sheela Bhatt.

Image: Uttam Ghosh