|

|

| Help | |

| You are here: Rediff Home » India » Movies » Columns |

|

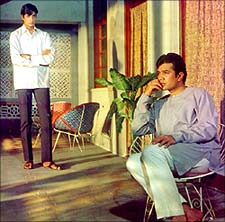

Hrishikesh Mukherjee | ||||

| Related Articles | ||||

|

•

Hrishida's best films

| ||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Last Updated: August 30, 2006 16:33 IST

Sunday morning, I changed the caller tune on my phone. Moved from an English oldie to Har seedhe raste ki ek, the fabulous title song from Golmaal. About eight hours later, a colleague messaged me the news, minutes before it took over the television channels. A lump hit my throat and I instantly flashbacked to last year, when I had called up Hrishida.

Working on a feature on India's best films, I couldn't look past Hrishikesh Mukherjee, the name tempting me from the film directory. Could I get an opinion from the man who made Anand? I called, and he picked up, huskily assuring me that it was he. I stammered out a nervous introduction and, making sure not to cut me off mid-sentence, the filmmaker finally stopped me. "I cannot help you, I'm sorry," he wheezed into the phone. "I am very ill." I hastily muttered an apologetic, awkward goodbye as the line went dead.

I was shattered and, I soon realised, heartbroken. Yes, filmmakers get old and their films live on. Yes, life goes on. But that this would happen to Hrishikesh Mukherjee somehow just hit harder. I felt helpless and greatly dismayed, and was resultantly puzzled. Not just had I never met the man, I also hadn't ever really read up or researched his background and technique. Yet, I felt inexplicably attached to him. All I had done, of course, was fall in love with the films he made. And that's all it takes.

There are filmmakers with a great cinematographic eye, those with powerful use of light and shadow, those who throw their actors over the edge to achieve mammoth performances and those who overwhelm you with sound and fury. In terms of emotion, Hindi cinema is packed with directors conversant with maudlin melancholy and rolling-in-the-aisles humour.

Mukherjee's cinema was beyond directorial technique, or storytelling. His are films with depth and one-liners, films with pathos and slapstick, films with farce and grand tragedy � above all, however, they are films bred in familiarity. Absolute familiarity. Wonderfully etched characters are drawn with such tender nuance that not only do we relate to them, they echo people plucked uncannily from our lives. From jobhunters in short kurtas to lanky alcoholics with telescopes, Hrishida's folk have been disarmingly real, even despite great caricature. You can't help loving them.

Mukherjee's cinema was beyond directorial technique, or storytelling. His are films with depth and one-liners, films with pathos and slapstick, films with farce and grand tragedy � above all, however, they are films bred in familiarity. Absolute familiarity. Wonderfully etched characters are drawn with such tender nuance that not only do we relate to them, they echo people plucked uncannily from our lives. From jobhunters in short kurtas to lanky alcoholics with telescopes, Hrishida's folk have been disarmingly real, even despite great caricature. You can't help loving them.

And it was not as if he drew his actors from the haughty sidelights of parallel cinema. These were superstars, not art-house critical favourites looking scornfully at the mainstream. He gave Amitabh Bachchan [Images] visibility in Anand, and subsequently balanced out his angry-young-man credentials with roles of acting significance. In 1973, Hrishida's Abhimaan rose alongside Prakash Mehra's Zanjeer; 1975 was the mammoth year of Ramesh Sippy's Sholay [Images] and Yash Chopra's [Images] Deewar, but Hrishida did his luminous bit with Mili and Chupke Chupke. His films might not have been Amitabh's blockbusters, but they do give us the megastar's most substantial performances.

The stories are literature by themselves. From immense marital discord to the inevitability of death, from delicate Wodehousean farce to war of the classes, he tackled it all but laced his movies magically with an earnest realism that touched us to the core. Special cinema of course, but crucially special sans fanfare. A Hrishikesh Mukherjee film didn't come with any massive pretentions of grandeur, any conceit of inaccessibility. This was dal-bhaat filmmaking, supremely fresh everyday slices of life, served up unfailingly warm and tender. The films he made discriminated not between frontbenchers and critics, cineastes and collegekids, critics and our mothers.

And how they endure. From Rajesh Khanna's babumoshaai to Utpal Dutt's eeesh, not to mention lyrical dialogues impossible to forget, the words penetrated the nation's collective lexicon. Even today, cable operators are well aware that their best chance of getting people to watch a poor-quality channel on a Saturday afternoon is to show one of Hrishida's Amol Palekar comedies. And the dramas are infinitely compelling, peopled by characters he turned into our extended family. The stories are ever poignant and never overdone, and we're repeatedly forced back into choking back a sob. Or stifling louder-than-acceptable guffaws with our hands. The magic lies, of course, in the fact that we are often torn by both emotions simultaneously.

And how they endure. From Rajesh Khanna's babumoshaai to Utpal Dutt's eeesh, not to mention lyrical dialogues impossible to forget, the words penetrated the nation's collective lexicon. Even today, cable operators are well aware that their best chance of getting people to watch a poor-quality channel on a Saturday afternoon is to show one of Hrishida's Amol Palekar comedies. And the dramas are infinitely compelling, peopled by characters he turned into our extended family. The stories are ever poignant and never overdone, and we're repeatedly forced back into choking back a sob. Or stifling louder-than-acceptable guffaws with our hands. The magic lies, of course, in the fact that we are often torn by both emotions simultaneously.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee was truly the heart of Hindi cinema. His films have transcended libraries and genre, and simply become a part of who we are. I grew a moustache recently and, despite the Mangal Pandey jibes, my predominant encouragement is drawn from Utpal Dutt's inimitable Golmaal lines on the importance of a man's mouch. I am not a man for funerals, but there are some cases where one just has to pay last respects.

The caller tune on my phone, needless to say, now stays, a tribute to the great humanist filmmaker. It is the kind of song that inevitably makes you break into a grin, but like Hrishida's cinema, the lump in the throat stays alongside the smile.

|

|

| © 2008 Rediff.com India Limited. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer | Feedback |