India emerge with honours

Daniel Laidlaw

The turnaround fashioned by India in the drawn fourth Test proved something of a microcosm of the series in which, ultimately, India emerged with the

honours.

At 336/2, a quickly-compiled England total in excess of 600, with resulting

pressure on India's batsmen to save the match and series, appeared close to

inevitable. But as the destiny of the series was turned around commencing

with the rearguard second innings at Trent Bridge, so too were the fortunes

of the fourth Test after the opening day.

It is unfortunate that the toss played such a crucial part in shaping the

decisive match. Given the placid nature of the pitch, the side batting first

was always favoured to virtually close the other out of the game, dulling

the edge of the contest. It could just as easily have been the tourists in

an identical position by the end of day one, and with the potential of

Harbhajan and Kumble to make the most demands on the batsmen, that would

probably have been the best chance of a result either way. Barring an

egregious calamity or something truly inspired, though, the balance of the

teams wasn't conducive to achieving a result within the scheduled time.

That shouldn't have meant being resigned to fate upon the fall of the coin,

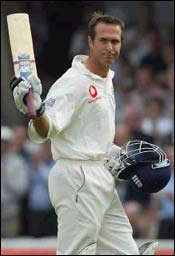

but there was an air of inevitability in the manner in which the immensely

confident Vaughan and company eased away. Frankly, it was surprising as many

as two wickets fell on the first day, such was the untroubled skill and

sang-froid with which Vaughan batted.

That shouldn't have meant being resigned to fate upon the fall of the coin,

but there was an air of inevitability in the manner in which the immensely

confident Vaughan and company eased away. Frankly, it was surprising as many

as two wickets fell on the first day, such was the untroubled skill and

sang-froid with which Vaughan batted.

India's hope lay in emulating Sri Lanka's Oval win in 1998, when an England

total of 445 was quickly surmounted and Muralitharan wreaked havoc. To

create even a remote chance of that, England first had to be limited, and

the catalyst was the utilitarian Sanjay Bangar.

Bangar appears an unassuming cricketer, a stonewaller as an opener and a

useful if modest medium pacer. He might be one of those Test players who is

selected for a handful of matches, performs respectably, then fades away

into obscurity. It seems unlikely he represents a long-term answer for India

as an all-rounder. But in the third and fourth Tests, at least, Bangar was

the embodiment of the principles required to succeed in England. From this

vantage point, Bangar was everything that Ajit Agarkar should have been but

was not. It may be telling that Ganguly elected to give him the new ball in

the second innings. Based on performance, it was certainly deserved.

Bangar, on day two, gave India a control over the tempo of the game that had

been previously lacking, the accuracy and discipline of his away swing

making a difference not just by itself but in the way it supported the

bowlers at the other end and made them, in turn, seem more dangerous. Ian

Botham may have mocked his lack of pace, but it was completely irrelevant.

In fact, it may even have been of benefit in that it caused him to suffer no

illusions regarding his role. In purposefully adhering to a consistent line,

Bangar instigated the recovery, trapping Crawley with one that seamed back

and having Hussain caught in the slips driving extravagantly. The benefits

of accuracy combined with patience amply demonstrated, Bangar opened the way

for Harbhajan to collect a five-wicket haul.

Replying to England's total, India's objective seemed clear-cut: aim to lead

by near 200 by the end of day four, leaving two-and-a-half sessions to bowl

England out on the last day and chase any extra runs. A distant possibility,

but one that could not have been considered beyond India's formidable

batsmen.

Rahul Dravid's comments indicated India envisioned scenario of this type.

"There is still a lot of work to be done and any of the three results are

still possible," Dravid was quoted as saying on CricInfo after day three.

"We will have to see how it goes, the first session tomorrow will be

crucial - if we don't lose wickets early on we can press on from there."

It seems unlikely that declaring behind England in the hope of forcing a

result was seriously considered. Despite the conjecture, it would have been

unrealistic and, moreover, unwarranted. Given how readily Nasser Hussain had

resorted to the defensive, India were unlikely to be set anything

approximating a generous target. Their best chance of winning lay in gaining

a lead and applying pressure to England's batsmen on a turning last-day

pitch.

Unfortunately, a potentially intriguing finish was ruled out when Laxman and

Dravid were not prepared to risk making a more concerted effort to press on.

After the early wickets were preserved, the pair was prepared to play some

shots, but only up to a point. Laxman at one stage had a surprisingly sedate

30 of 120 balls and considering the onslaught carried out in the Headingley

gloom, it was slightly disappointing he did not show more initiative.

Hussain's short-pitched tactics on day three, and Caddick's remark that

England had done everything they could, showed that England had already

virtually resigned themselves to a draw. Ultimately, rain ensured none of it

would have mattered anyway.

Rahul Dravid and Michael Vaughan were the outstanding players of a

batsman-dominated series. Dravid grew in stature and presence as the series

progressed and his innings' became increasingly compelling. Rarely receiving

the encomiums of others, Dravid, like his team, started the series

diffidently before flourishing.

Dravid's understated, almost humble, and yet indomitably resolute efforts

saw him not so much dominate as endure, a fixture which India's innings were

built around in each of the last three Tests. His influence is reflected in

the fact he was involved in 7 of India's nine century partnerships in the

series. In short, he displayed tremendous character, and after threatening

to make a huge score several times did just that in the last Test, for once

standing out by himself.

Notwithstanding continued changes at the top of the order, India's batting

came to impose itself on the series. By the time of the second innings at

Trent Bridge, Dravid, Tendulkar and Ganguly rose to the level required of

them and England's attack, after realising India could not be thwarted

through discipline alone, lacked the venom to make inroads. The return of

Caddick did not improve it and without Simon Jones or, bewilderingly, the

unselected Steve Harmison, India increasingly had their way, never more so

than in the epic first innings at Headingley.

Notwithstanding continued changes at the top of the order, India's batting

came to impose itself on the series. By the time of the second innings at

Trent Bridge, Dravid, Tendulkar and Ganguly rose to the level required of

them and England's attack, after realising India could not be thwarted

through discipline alone, lacked the venom to make inroads. The return of

Caddick did not improve it and without Simon Jones or, bewilderingly, the

unselected Steve Harmison, India increasingly had their way, never more so

than in the epic first innings at Headingley.

With Dravid, Tendulkar and Ganguly more than matching England's output,

India's attack, specifically Harbhajan and Kumble, became more threatening.

At the beginning of the series, the lack of experience (and quality) of

India's main seamers appeared likely to undermine the tourists, and so it

proved. Once the bowling emphasis shifted to Harbhajan and Kumble, though,

India's attack had a dimension to it that, certainly if bowling second,

bettered England's.

Too closely matched to produce a winner, by series end India had the firmer

grip on the contest. The tour may not have brought the watershed away series

victory, but more of the pieces came together to make it very close to being

realised. Drawing 1-1, in England, against a team that rates itself a chance

to wrest back the Ashes, must be seen as an encouraging, and deserved,

outcome of an auspicious tour.

More Columns

Mail Daniel Laidlaw